If you ever stand on a shallow sand deposit and try to determine, whether it’s a sandbank or not, you’re not the only one wondering about it. The EU habitats directive tells us that the Natura 2000 habitat 1110 sandbank is predominantly shallower than 20 m and is always covered by water, and it may or may not have unique or not so unique vegetation. They should also be mostly surrounded by deeper water.

If you look at these conditions, they are very vague and easy to interpret any way one likes. In the northern Bothnian Bay, sandbanks have historically been interpreted from aerial photos and they are mostly extensions of sandy beaches. A sandy beach is a Natura 2000 habitat as well, and the beach ends at the water. According to the description, a sandbank will start only after the lowest low water but not from the beach directly.

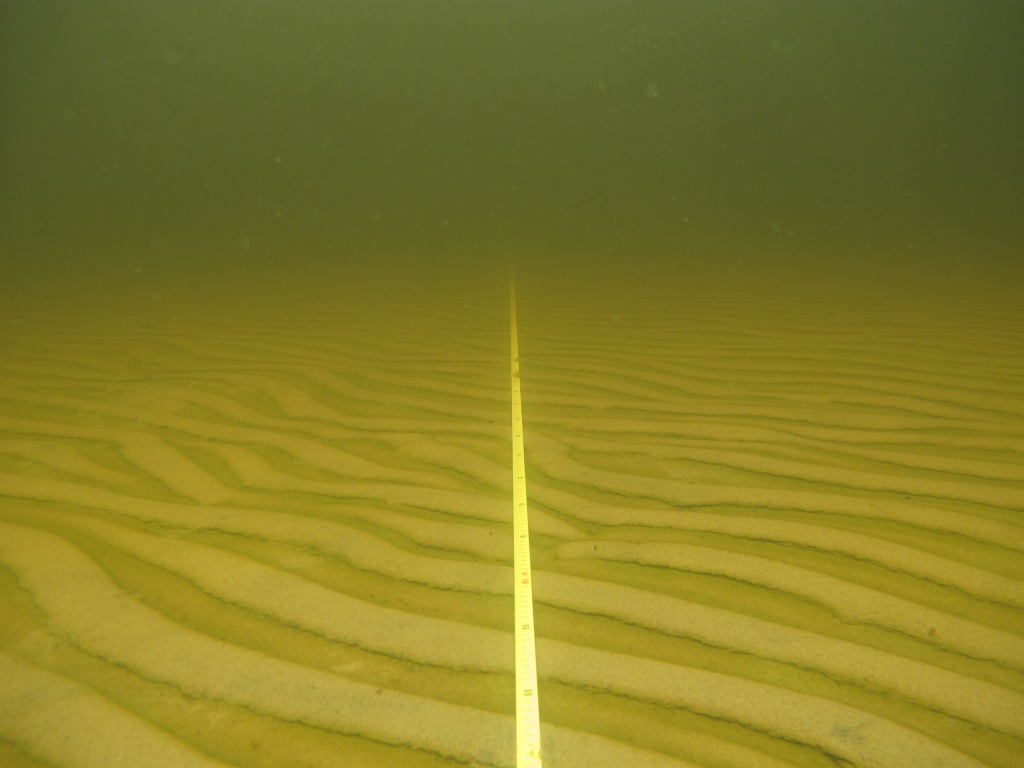

In southern Finland and Sweden, sandbanks often have a lush vegetation. For example, Zostera marina, the eel grass, can indicate a sandbank, even though eel grass meadows mostly grow on flat sandy bottoms and not on elevated banks. In the northern Finland and especially in the SEAmBOTH area, sandbanks often have no vegetation at all. They are either too deep for any green flora or they are too exposed and thus too movable for any rooted vegetation to stay put. The sand is constantly moving with the wave action in the shallow areas and that makes it difficult for plants to take root.

Sandbanks have been modelled because we still don’t know enough of them to put them on the map from the field observations only. The problem with this is, again, determining what is a sandbank and what is not. I was once looking at a map of modelled sandbanks in the northern Bothnian Bay and was wondering where some of the largest sandbanks on the Finnish side had disappeared. It turned out, that for the modelling purposes, a diameter of 5 km or less was used, and for example Pitkämatala and Suurhiekka are larger than that. They didn’t get modelled as sandbanks just because of their enormous size.

Also, consider the description “slightly elevated”. What does that even mean? Especially if Zostera meadows count as sandbanks, regardless of elevation from the surrounding area. Merikalla is a large sandbank and a Natura 2000 area at the border of the EEZ of Finland. It rises ever so slightly from the surrounding sandy bottom and sometimes you find it modelled as a sandbank and sometimes not. The area is designated as a Natura 2000 area for protecting the sandbank, though.

If you find a shallower sandbank in the SEAmBOTH area, you might find typical vegetation to be tiny little Charales algae or mini-Potamogeton perfoliatus. If the plants grow very large, the chances are, that you’re not looking at a sandbank at all but a shallow bay or a lagoon with a sandy bottom. The exposed sandbanks rarely have any larger vegetation on them because of the harsh conditions of rolling sand grains and wave action.

In the north, sandbanks are mostly geological features. Sure, there might be a lot of micro and nanobenthos, tiny little creatures and critters that can not really be identified with a regular microscope, but anything bigger than that is susceptible to the wave action.

As a diver, I still enjoy diving on a bit deeper sandbank, with or without the vegetation. The wave action creates beautiful waves to the sand and if you catch the sun’s rays playing on the sand with them, it’s pure magic.

Written by Essi Keskinen, Metsähallitus